All content of this website is under copyright and subject to all laws thereof. If you are unsure how to properly cite copyrighted material, refer to your style manual or feel free to e-mail me at bookcrazed@yahoo.com.

by Janice Stensrude

published in A Mystic Call – Naming the Spiritual Condition of the

World: Proceedings of the Second Annual Gathering of Friendly

Mystics. (Blue Bell, PA: What Canst Thou Say, 2015.)

The term "mysticism" has Ancient Greek origins, with various, historically determined meanings. Derived from the Greek . . . meaning "to conceal," it referred to the biblical, the liturgical and the spiritual or contemplative dimensions in early and medieval Christianity, and became associated with "extraordinary experiences and states of mind" in the early modern period. ("Mysticism," Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Mysticism)

The Society of Friends is perhaps the most remarkable demonstration in history of the availability of mystical experience to groups of open but otherwise ordinary people. (John Ferguson, Encyclopedia of Mysticism)

There is no better way station on the path to mysticism than a Quaker meeting. (Me)That Sunday afternoon at Earlham when Wayne rejected my simplistic definition of a mystic—"anyone who has mystical experiences"—was the first time I had thought to challenge my generally simplistic approach to the entire topic of mysticism. Evelyn Underhill's long list of the requirements for those who might aspire to be a mystic would bring any simple-minded approach to the subject to its knees. In the first 139 of her more than 500 pages, I noted five occurrences of the term "true mystic," each one an introduction to a discussion of the genius and difficulties behind being a "true mystic." She wrote:

We do not call every one . . . a musician who has learnt to play the piano. The true mystic is the person in whom such powers transcend the merely artistic and visionary stage, and are exalted to the point of genius. . . . [Mysticism is] a complete system of life carrying its own guarantees and obligations. (p. 75)Geez! No wonder I got called on my ridiculously brief definition.

"Evelyn Underhill [1875-1941] was an English Anglo-Catholic writer and pacifist known for her numerous works on religion and spiritual practice, in particular Christian mysticism," Wikipedia told me. Rufus Jones (1863-1948)—Quaker philosopher, educator, and mystic—listed Underhill as one of a half dozen or so scholars that he recognized as authorities on mysticism. Jones was Underhill's contemporary and is my go-to Quaker philosopher and favorite Quaker author. If one of my primary thought heroes endorsed Underhill's work, I couldn't easily dismiss what she had to say.

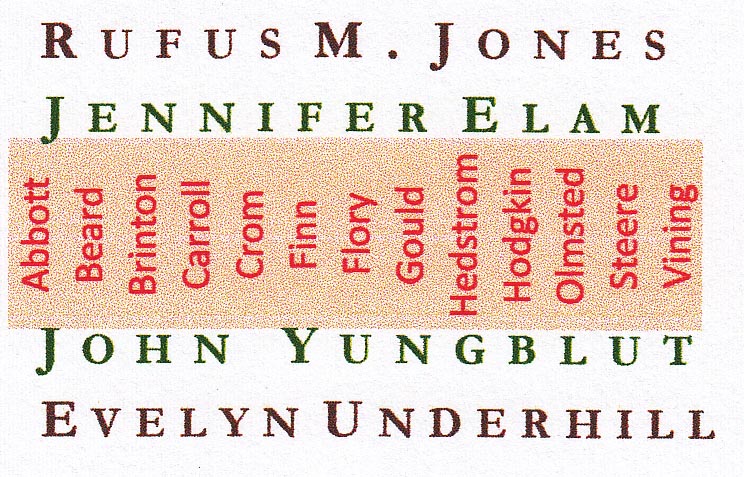

The mystics about whom Underhill wrote were all "great mystics." The mystics about whom Quaker Jennifer Elam wrote in Dancing with God Through the Storm—the more than 100 people she interviewed about their mystical experiences—were like people I know. In retrospect, I can see that Underhill and Elam form the perfect sandwich for the serendipitous collection of mystical writing I was about to ingest.

Matthew Hedstrom, Assistant Professor of Religion at University of Virginia, called attention to an article in the October 11, 1948 issue of Time that reported the publication of two "quietly stirring" new books on mysticism, one by the young Thomas Merton, the other by Rufus Jones, who had died the previous June. Hedstrom quoted from the Time article: "Both men re-emphasize two facts often forgotten: the world still has millions of mystics, and the most mystical human beings are often among the most practical as well."

In 1930 Jones had estimated that for every known mystic, there were perhaps unknown hundreds quietly going about God's business. By 1944 he had seen the numbers much greater: "Where there has been one mystic who has put his experiences into literary form there doubtless were a thousand who had the vision but who did not write."

From hundreds in 1930 to thousands in 1944 and millions in 1948. What a relief! Most of what I had been reading that used the term mystic were discussions of the lives and characteristics of long-dead religious figures—most frequently Catholic saints, but with a fair assortment of their non-Christian contemporaries thrown into the mix. This group, who lived during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (with a few notables in the fifteenth century), were the prototypes of mysticism, and when writers wrote simply "the mystics," this is to whom they referred.

So there were living mystics at the time of Jones's death in 1948 and at the time of Elam's research that was published in 2002. With Elam on one side and Underhill on the other, I began to add layers to my mystical sandwich. The Jones layer was added atop Elam. On the Underhill side I soon added a layer of John Yungblut (1913-1995).

Yungblut was a Quaker writer and scholar of Quakerism and Jungian psychology. He came to Quakerism after a 20-year career as an Episcopal priest and, like Jones, had an impressive education, as well as an impressive list of publications. Though a younger contemporary of Jones, his views on the stuff of which mystics are made was more conservative, yet still in line with many of today's writers on mysticism. First, he narrowed the field of what could be considered mystical experience:

It is much easier to say what mysticism is not, than what it is. The essence of the mystical experience has nothing to do with the occult, the esoteric, extra-sensory perception, spiritualism, hearing voices or seeing visions, with all of which it is sometimes confused in the popular mind. The most that can be said is that mystics are sometimes the kind of persons who may also be psychics and who may hear voices or see visions. But some of the greatest of the mystics have not experienced any distractions in these directions, and others, like John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila, have been very wary of the messages so received. (Quakerism, p. 5)Jones, on the other hand, offered a broader definition:

The word "mystic," as I shall use it, stands for a person who insists on a somewhat wider range of first-hand acquaintance with reality or of direct experience than that which is confined to the operation of the five or more special senses. (Some Exponents, p. 15)Jones's definition foreshadows the spiritual revolution that birthed the New Age Movement. His largesse became a powerful tool in his life's work—first, bringing together the splintered Religious Society of Friends and, second, participating in (if not birthing) an ecumenical spirit among many different religious groups through the common thread of mysticism. Hedstrom wrote:

Jones, both as scholar of mysticism and through his personal example and activism, promoted an egalitarian mysticism, open to all. Mystical union with the divine, according to Jones, was not a privilege reserved only for the great spiritual athletes. But Jones did not just theorize—he also popularized. His willingness to market himself to the masses was a critical stimulus towards the popular embrace of a mystical emphasis in liberal Protestant spirituality, both because of his own direct influence and because of his influence on even more popular writers such as Howard Thurman and Harry Emerson Fosdick. This middlebrowing of mysticism paved the way for the success of a wide range of mystical writers to come, starting with Thomas Merton and lasting into the New Age. (para. 2)Jones was not the only writer to speak encouragingly of mystics in the present tense. Rebecca Beard—Quaker, physician, faith healer—wrote three books in the early 1950s about "spiritual healing." Her emphasis was on prayer and positive thinking, but she was a great admirer of Rufus Moseley (1870-1954), whom she dubbed "a great modern mystic" (Goal, p. 92)—not the great modern mystic, but a great modern mystic. In her book, mystics came in multiples, again confirming that all the mystics weren't dead after all.

My mystical sandwich was completed with a rich filling of Beard and the other Quaker writers I read. When finished, it looked like this:

Emotional Crises and Mystical Experience

In my reading, one point of agreement among all writers was that emotion is more important than intellect in the making of a mystical experience. In the battle between heart and head, it seems, mysticism thrives when the heart dominates. Underhill wrote about the "act of perfect concentration" that is created with intense emotion:

It is a matter of experience that in our moments of deep emotion, transitory though they be, we plunge deeper into the reality of things than we can hope to do in hours of the most brilliant argument. . . . passion rouses to activity not merely the mind, but the whole vitality of man. It is the lover, the poet, the mourner, the convert, who shares for a moment the mystic's privilege of lifting that Veil of Isis which science handles so helplessly, leaving only her dirty fingermarks behind. (p. 48)Elam wrote that many of her research subjects reported mystical experiences at times of emotional intensity. "New openings or deepenings (further openings to God) appear to occur most often during times of stress, loss, grief, trauma, or when we are feeling overwhelmed," she wrote.

I, too, found this to be true among those who shared with me their stories of a brush with God. When I think of the people I have known who reported mystical experiences, I see mostly a pattern of dramatic response to intense grief, fear, or unbearable disappointment.

I think of Brian, a plastic surgeon who grew up in a secular Jewish family and knew very little about the faith of his Jewish ancestors and nothing at all about other faith traditions. He was a self-described "staunch atheist." "I knew people who had a deep and abiding faith in something greater than themselves, and I thought they were fools," he told me.

Brian had a good reputation, a thriving practice, and he loved his work. Following the death of his wife from a lingering cancer, he suffered a dark period, not just from the grief of his loss but also from the finally acknowledged fact that he had been one of those men who spent his days as a hero healer and his evenings as a perpetrator of unspeakable domestic violence. The only witness to his secret was dead, but the guilt he kept hidden away began to fester.

In a fit of anguish, his head seemed to burst open, and he experienced a stunning white light, and, he told me, "suddenly I had inner knowing." That inner knowing included long passages of text that he later identified as parts of the Christian bible. After friends in whom he attempted to confide accused him of doing drugs and being deranged, he said, "I finally decided to just trust my own experience instead of going crazy."

Brian's response to his experience was to plunge himself into a study of the great spiritual traditions, learning about the teachings of Jesus and other great spiritual teachers. He built a surgical suite in his offices, where all but the more lengthy surgeries could be performed in an environment created to minimize surgical trauma and maximize post-surgical healing. Brian and his surgical team wore brightly printed scrubs, and patients were invited to address everyone on a first-name basis. A large picture window looked out on a private garden, the room was filled with crystals, and calming music was played during surgery.

Brian told me that when he added "holistic approach" to his business card, he expected his medical colleagues to accuse him of going round the bend, but instead they began saying that he was "crazy like a fox," cashing in on the New Age craze. "They stopped referring their patients to me," he said, "but they continued to send their family."

Brian remarried and stayed loyal to his awakening for some time. He closed his medical practice, as he had planned, and became involved in hospice work, which was a goal he had set after Spirit had shaken him awake. It was more than ten years later that I heard rumors that he and his wife had divorced and he had dropped out of sight. Perhaps it was his time for another dark night of the soul.

Al's experience was oddly similar to Brian's with its white-light vision and Christian scripture content. Al was a member of a motorcycle club, a euphemism for the motorcycle gangs that flourished among young men searching for camaraderie and a personal sense of power and belonging. As a real-deal mechanical genius, he easily carved out a position of value within the club with his skill at motorbike repair and a talent for designing and sewing the leathers that the riders wore. At first Al denied the questionable activity of some of his club brothers, then simply turned a blind eye to it. But the ugliness of the truth eventually caught up with him when he witnessed a gut-wrenching act of violence.

Fearing for his life if he simply walked away, Al began to have sleepless, nightmare-filled nights. He couldn't see a way out, and one evening drove out into the countryside, sat on the side of a hill, and placed a revolver in his mouth. A great rushing noise surrounded him, and he found himself in a ball of intense white light. The air was churning with pages that looked to be torn from a book, and when he looked at them, they were filled with bible verses. Unlike Brian, the words were familiar to him from his childhood years attending Sunday School at a little neighborhood church, where his minister emphasized the importance of scripture and handed out prizes to reward the children for memorizing bible verses.

The next thing he knew, he was awakened by the sun coming up over the horizon, and the revolver, with its bullets still in the chamber, was at his side. He rode to his mother's, where he slept, prayed, and searched the bible for answers. God had intervened in his suicide, he told me, and strengthened with that belief, he returned to his club and, without embellishment, told them he had been born again and that the Lord had instructed him to leave the club and devote his life to Christ. With grateful and astonished surprise, he accepted their unexpected good wishes, revved up his Harley and began a new life.

Al married twice, divorced twice, and had four children. When I met him, he had a disabling marijuana habit and had not seen the young children from his second marriage in several years. Among his friends and neighbors, he was known as a kind and generous person who often gave of his time to those who needed an old car repaired or a patch on their roof. Once, he said, he saw a homeless man on the street that he recognized as an angel, and he gave him his guitar. That was the closest Al came to again experiencing a feeling of the presence of God in his life.

I propose that the emotional response to crises creates a powerhouse of emotional energy that opens the heart to spiritual truth. Strong emotions create the focus required to etch positive change into our daily lives. For some, the change is temporary; for others it marks the beginning of a new and more meaningful life path.

Quaker writers nearly always mention the goal and earmark of mystical experience is the fruit it yields, its "social utility," as Hedstrom put it (sec. II, para. 5). Quaker Howard Brinton wrote that ethical mysticism is communion with God followed by a commitment to serve the world.

Elam also found this spirit of altruism among her research subjects: "For many people, the experience of union with God is the beginning of a journey back into the world to do that work which is now both God's and their own." This confirms my own observation that the mystical experience inspires gratitude and a strong desire to participate in the creation of a better world. The good behavior is not a bargaining chip or pay back for a Divine favor. It is a deeply felt desire borne from the mystical experience, as if the experiencer had been inoculated with Divine Love.

I am reminded that George Fox's vision on Pendle Hill was a classic case of emotional breakthrough and a classic case of follow-through. From that point forward, his God antenna was up and working, and he never flagged in his determination to build a new religion based on truth.

Born or Made?—Nature v. Nurture

Is it in the DNA or in the effort? Are mystics born with a gift for mysticism or developed through a disciplined approach or practice?

Most writers on mysticism suggested that the ability to engage the Divine is inherent, though often (or usually) undeveloped. Yungblut wrote: "The mystical faculty, whether developed or not, resides in all men and women by virtue of our shared humanity" (p. 11). Underhill, though consistently adamant on the connection between a genius gift and mysticism, wrote of a "natural mysticism . . . that is latent in man" (p. 13).

The first thought that came to my mind as I pondered the question was Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner proposed that the usual general intelligence tests overlook some specific types of intelligence. Originally naming seven intelligences, his list has expanded to nine: Visual/Spatial, Verbal/Linguistics, Mathematical/Logical, Bodily/Kinesthetic, Musical/Rhythmic, Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, Naturalist, and Existentialist. According to Gardner's theory, each of us is a unique combination of these intelligences.

The second thought that occurred to me was a statement made by David Bayles and Ted Orland in their classic Art and Fear: "Even talent is rarely distinguishable, over the long run, from perseverance and lots of hard work."

So which of these concepts could be applied to mysticism? Gardner's Theory of Multiple Intelligences that implies that each of us is born with a package of special gifts that in some way sets us apart from others or Bayles's and Orland's assertion that practice makes perfect, that putting in the work is as good as being born with the gift?

What I have always found appealing about Gardner's theory is that it allows people to be differently gifted, rather than more or less gifted. Jones, champion of the common person as mystic, seemed to agree with this judgment—at least so far as it applies to mysticism—when he wrote in 1930:

It is not easy to tell why some persons are so much better organs of the life of God than others are. Perhaps, however, it is no more mysterious than is the fact that some substances are vastly better conductors of electricity than others are. (Some Exponents, p. 54)I agree with Jones, and I suspect that both perseverance and native talent are at work in creating a mystic. A "great mystic" may be one who is born with a gift and works to perfect it, or maybe even someone who had practiced the skill with intense effort over a long period of time . . . and if they are judged by the Quaker measuring stick, they are also contributing mightily to the betterment of the human condition.

This leaves room for lesser mystics, I should think—good ones and pretty good ones and just ordinary ones. I can't imagine a category of "not very good." Living in the knowledge of the presence of God may hopefully one day become ordinary, but I cannot see it ever being "not very good."

"The Mystic Way": The Path of Spiritual Practice

For so long, I have associated a practice with daily yoga or meditation or a combination of the two. These practice forms have dropped in and out of my life over the past fifty years. My prayer of gratitude is the only practice that has consistently endured, becoming so entirely a part of my life that I rarely take a bite of anything without my ritual prayer. It's brief, complete, and from the heart—and I have the opportunity to practice it three times a day most days.

Until I began this search for a definition of "mystic," I had not given any thought to following any particular practice for the conscious purpose of finding my way towards what seemed to be already magnetically pulling me in its direction. For a few years I practiced Transcendental Meditation (TM)—a twice daily 20-minute discipline that involved chanting a mantra—until a gaggle of changes conspired to disrupt my ordered life.

Some years later, I undertook an experiment to see if I could reduce my sleeping time. I began taking a 15-minute nap every four hours, working towards a goal to omit the longer period of sleep at night. Not being a napper by habit, the challenge for me was to clear my mind of busyness as rapidly as possible and reach a sleep state. I used the old trick of progressively relaxing my body, beginning with my toes and ending with the ends of my hair. At the same time, I would chant over and over: "I am falling into a deep and peaceful sleep. When I awaken I will feel relaxed, refreshed, and rested."

I never succeeded at achieving a sleep state in 15 minutes, nor did I achieve my ultimate goal to essentially eliminate nighttime sleep, but I did reduce it to six hours of deep, refreshing rest. It occurred to me, after the fact, that my relaxation practice was a variation of my earlier meditation practice. I gave up the project when my business became too demanding to allow me the luxury of leaving my office during the course of my workday.

One day in December 2002, near the dawning of an Australian summer, I hiked up the steep hill from my apartment to the local Quaker meetinghouse for the first time. It was a fitting metaphor and the beginning of a new experience of the Divine. I had not yet heard that Quakerism is a "mystical religion" when I began to feel "the presence in the midst." A print of the painting by that name hung over the fireplace in the worship room of the large 1919 Australian Federalist-style brick bungalow.

I suppose the worship room had been the living room when it had been the home of the well-to-do spinster—as they labeled single women in those days—who lived there from the time it was built until the Quaker meeting purchased it 43 years later. Across the wide entry hall, with its soaring ceiling, was the meeting's library of nearly 2,000 books. The library must have originally been the parlor. It and the master bedroom were the only two rooms in the house that had lovely ceiling moulding and magnificent plaster ceiling roses. That beautiful room, ringed with shelves bursting with Quaker thought and experience, made almost as great a contribution to my growth in Quakerism as the meetings for worship . . . especially after I was invited to serve on the library committee. I was a cat locked in a catnip garden. Always there were a few books I was in the progress of reading, a short stack of books that I wanted to read, and a long list that I hoped to get around to some day. I was immersed in Quakerism.

I missed very few Sundays after that first trudge up Mount Lawley. Quaker meetings are brain trusts, as well as spiritual trusts, and I looked forward to every hour of worship and every hour of tea and biscuits that followed. When I read Robert Barclay's words, they mirrored my experience:

. . . when I came into the silent assemblies of God's people, I felt a secret power among them, which touched my heart, and as I gave way unto it, I found the evil weakening in me, and the good raised up. (Steere, p. 1)I often experienced that of God among us, within us, and around us. And on a few occasions I came to know the meaning of a "covered meeting."

Quaker meetings were providing me with another sort of practice—the deep, silent centering that constitutes an hour-long meeting for worship, as well as a shorter version at the beginning of other sorts of Quaker gatherings. Margery Post Abbott wrote beautifully about just this sort of experience. She found that Meeting for Worship for Business was another place where "we practice being mystics." She wrote: "As we do our corporate business, we learn and practice ways by which we can bring a sense of the Holy into everyday life—in short, how to live our faith" (p. 29).

Though my personal mystical events were infrequent, I was a member of a group mystical experience most Sundays for the eight years I attended Mount Lawley Recognised Meeting . . . only a short walk up a very steep hill.

Hanging out with Quakers and dipping into their written wisdom has added bits of discipline to my messy collection of practices that have gradually moved me into a more frequent connection with Spirit. In Beard I found advice on a positive attitude, which prepares the mind for physical and spiritual health, as well as a description of her own disciplined schedule of prayer and meditation to bring her into alignment with God's will. The aging brain brings many gifts—I am much more adept at "the big picture"—but sometimes it's a trade-off. I struggle to focus well enough to accomplish a deep meditative state, yet I continue to have my flashes of insight. Mostly they come as I wake in the morning or when I sit in worship with others.

Yungblut's advice to "all Friends who are embarking on this venture of becoming a contemplative" reads with such urgent encouragement that I present it here complete:

. . . begin a disciplined study of the writings of the apostolic succession of Christian mystics, beginning with the great New Testament examples, Paul and John. These were an authentic company of experimentalists. We need to be familiar with the range and variety of mystics in the tradition. Not all of them will speak to everyone's condition. But if we will stay with this discipline we will find companions along the way to guide and direct our path. Little by little we will recognize that we belong in this company, that they constitute for us "the cloud of witnesses," and we will gradually discover what special kind of mystic each of us is. (Speaking, p. 22)As a lover of books and a miner of fine minds, I've already begun to take that advice. But if that's not your cup of tea, if you're comfortable with your own serendipitous group of practices that doesn't include long forays into difficult reading, then keep on keeping on. There are many "pathways to the reality of God," Jones reminds us with his 1931 book title. We can take a sound and simple bit of counsel from TV's leading pop psychologist, Dr. Phil: "Behave your way to success."

Am I a Mystic?

Until I began to read What Canst Thou Say? I hadn't thought much about my experiences with the Divine as being mystical. I even thought of them as relatively common. Nearly everyone I spoke with had their own story of spiritual inspiration or intervention. I did discover, though, that having one such story was acceptable, having two or more was not. Temporary insanity happens to everyone now and again, but recurring insanity is a horse of a different color.

I am apparently not alone in not having given much thought to the mystic title. Jennifer Elam found that a significant number of her research subjects, while believing they had genuine mystical experiences, did not consider themselves mystics or had not thought about calling themselves mystics. Others held the title in awe, while still others embraced the notion of being a mystic. Without ever representing myself as such, I think I may have begun to think of myself as a mystic at some point after I began hobnobbing with others who had mystical experiences, and were equally hungry as I was to talk about them without being knighted with that other label that is often assigned to us: Whacko.

There is a kind of mysticism that can only be granted as a sort of sainthood, after death, by a grateful many. Then there is that simpler mysticism that can be claimed by any who know in their soul they have been visited by God.

I think I can call myself a mystic, though certainly not a "great mystic." History reserves the right to assign such magnificent titles. I am just someone who experiences the spiritual presence that some have named God and hopefully am a better person for it, a person who serves the community of human beings in ways that make life more meaningful and joyful . . . one person at a time.

Some mystics are born to the experience, some come to it through diligent practice, and others are scared into it. I suppose I would consider myself to have experienced all three avenues. I remember that feeling of certainty of the Divine from my earliest memories; in adulthood I rediscovered the connection during a time of great stress; and because of Wayne's queries and my attempts to address them through my recent reading, I have a deeper understanding of the value of an intentional practice.

I do not aspire to the Ecstasy, only to a life of purpose and servitude to Divine will. I have chosen Quakers to accompany me on my journey. As Yungblut wrote:

We [as Quakers] are the inheritors of a mystical faith. And we are, all of us, born mystics, whether or not we have yet been concerned to cultivate the faculty that God has given us, the faculty that constitutes in us his continuing creation, even its evolving edge in man. God grant that we may aspire to become contemplatives right where we are, here "where one stands," you and I! (Quakerism, p. 23)I feel immense gratitude for Wayne's questions. Looking for answers has truly disturbed my life—booting me another league down my path.

Writing about our experiences will never be adequate. Mysticism as union with God is beyond words—but we try.